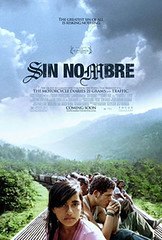

Sin Nombre, written and directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, is a film that has been in my head since seeing it yesterday. It's a magnificent, uncompromising film and I do hope it does well at the box office, as it is Fukunaga's directorial debut and an extraordinary one at that. If you've seen El Norte, you'll instantly recognize the story and perspective that's taken here. Yet stylistically, El Norte is rooted in magical realism, whereas Sin Nombre adopts a neorealist approach to its subject matter. I can't really decide which I like more, but I feel both are valuable portraits of South and Central American immigration. While mulling it over in my mind, I couldn't help but think about the critics' darling of 2008: Slumdog Millionaire, and perhaps this is the result of repressed honesty on my feelings towards that film. More on that later.

First, a bit on Sin Nombre:

Sin Nombre tells two stories that eventually converge. Willy is a member of La Mara gang, and his young friend Smiley is a new recruit, having passed his initiation by members of the gang kicking him until he can barely walk and is covered with blood. We are brought into this seedy underbelly of society and witness horrific acts of violence as the two friends try to prove their worth. Willy has a girlfriend, Martha Marlene, who he keeps secret from the gang. When she is discovered, she is accidently killed by Lil' Mago (one of the gang lieutenants and reminiscent of, wait for it... Lil' Dice from City of God) when he tries to rape her. Willy eventually kills Lil' Mago, and in the process, meets Sayra, her father, and uncle. They are a Honduran family fleeing north to a better life. The rest involves an attempt to escape the grasp of La Mara and cross the border northward.

That the scenes depicting gang life are grisly and uncomfortable is to the film's advantage, I think. Cinema, by in large, falls into two categories regarding acts of violence these days: glossing over it, or exploiting it. Sin Nombre is a hard-nosed portrait of gang life that neither sugar coats it, nor fetishistically revels in it. The result is a film that approaches its subject matter realistically and pragmatically. In this sense, the film draws from the strengths of neorealism: commonplace characters (many extras here were cast on location) with simple, realistic goals, plausible situations, and a clear, focused narrative.

What the movie accomplishes very well, I think, is a strong contrast that mirrors the impetus to emigrate in the first place. In the beginning, for instance, the film jumps back and forth between the stories of Willy and Sayra. With that staggered narrative comes an undulating sense of comfort. With Sayra and her family, we feel safe. With Willy and El Mara, everything feels dirty, grotesque, and dangerous, and there is desire to leave those scenes at least on a level of comfort. The scene between Lil' Mago and Martha Marlene is perhaps the most potent and horrifying, in part because you can see it coming before it ever happens, and because it is an unflinching, honest representation of reality. That she is killed almost becomes a reprieve for her as well as the audience, yet the possibilities between living in a gang (where it seems everything, women included, is communal and shared) and death are not a choice that anyone should have to make. In a way, she is spared from a life of humiliation.

The imagery and look of the film are exceptional. This type of movie hearkens back to older, on location methods of filmmaking.

The dynamics and camaraderie of the immigrants hitching a ride on top of trains is a miraculous image, and the one that first piqued my interest in the film. What the film does is simply observe this community, furthering its neorealist approach while creating images of events that are happening right now as I type this. The image, for me, is both surreal, yet documentary. It is Werner Herzog who says:

"What this world needs is more images, and that is something I am trying to work on."

Somehow, I think he would approve of Cary Fukunaga and Adriano Goldman's final product. Sin Nombre is a film that presents a dichotomy; a world that is both startlingly beautiful and hideously grotesque. Because of this, the film feels complete. It does not drag us deeper into despair with no hope, nor does it gloss over the horrors in false feel-goodness. I think it is because of the neorealist approach that it manages to work so effectively. Sin Nombre is a film that I hope does well, and I will certainly be examining it more in the future.

Everybody Loves Slumdog:

I'm going to be brutally (more like tough-lovely) honest. I don't love Slumdog Millionaire and I certainly don't offer laudatory praise, like so many others. I see it as Hollywood kitsch disguising itself as independent, international cinema. I just don't see what the praise is all about. By no means did I hate it, and I actually found quite a bit to like, but I kept asking myself: What exactly is this film trying to do?

I have heard of Slumdog Millionaire being called a brutal portrait of the Indian slums, which I'd only agree with if by "brutal" you mean "fantastical." It is not uncompromising, but rather caters to the audience's ultimate desires rather than ground itself in reality. Is it a bad thing to eschew reality? Absolutely not, but for me, Slumdog Millionaire amounts to little more than a child's fairy tale disguised by violence and shit-covered children because of this.

There's one problem I had: The film defuses any discomfort the audience has through comic relief, thereby lessening any messages to be had (which the film is clearly trying to convey). There is so much gloss and diffusion of reality that it's difficult to glean anything profound from the film. This is evident nowhere more than when Jamal, who sees his Bollywood hero in the distance, must crawl through raw sewage and water to get there. Is there supposed to be something funny about this? The audience I was with roared with laughter. Haha! Look at the little shit-covered Indian boy! Don't you find that funny? I sure do because I'm an American bourgeois living in my suburban home, driving my kids to soccer practice in my Volvo station wagon and I won't ever have to see anything that ludicrous in real life! Now the question is, was that reaction by the audience a misinterpretation of what the film was trying to do or did the film want to elicit that reaction? Judging by the timing and the editing, I think it's pretty clear the audience was supposed to have that reaction. For me, that doesn't make sense, I don't find that funny, and I don't really know what the film was trying to accomplish with that little stunt.

Another thing that annoyed the hell out of me was the cross-over to english as well as the bizarre subtitles. I can actually understand, allegorically, the importance of the crossing over to english as a parallel to India's westernization, but I get the feeling it was merely another way in which the film caters to the audience. That brings up the question: why is catering to the audience a bad thing? To answer that, I would say that it is not a bad thing necessarily, but it is overused. To some level, you have to give some sort of comfort level to the audience otherwise you risk losing them entirely. What abusing this does, however, is create a sense of complacency in the audience. I think the expectation of a happy ending is so ingrained in audiences today, that any movie that dares to have a sad one is largely deemed "bad" or "okay."

The subtitles, I hear, were jazzed up with colours and would appear next to whoever was talking because the director wanted to engage the audience more. Mostly, however, I found this distracting, and somehow I doubt Danny Boyle was trying to make some profound statement about that. Shots that call attention to themselves (or fancy-schmancy shots, as Wilder would put it) have their place in cinema. But lately, I feel this "Queasy-Cam" effect is sweeping the industry in all the wrong places. What, exactly, does incorporating distracting elements to a dramatic picture do for the movie? Ah yes, that's right, it distracts us from the weakest part of Slumdog Millionaire: the dramatic arc of the story and its characters.

I don't see Slumdog Millionaire as much more than a fantasy that almost completely glosses over the horrors of slum life. It is a fairy tale with destiny as its ultimate message (or something, I'm not really sure). Every character we are supposed to like is absolutely gorgeous. Even the Who Wants to be a Millionaire? host is a sexy version of Luis Guzman.

For me, the most annoying aspect of the film was Jamal. James Berardinelli writes:

"Boyle's feature draws the viewer in, immersing him in a fast-moving, engaging narrative featuring a protagonist who is so likeable it's almost unfair."

This, I don't understand at all. What exactly, is so likable about Jamal? I found the character underdeveloped and simple-minded to say the least. The relationship between Jamal and Latika, that is buried under great physical distance, a lot of quite cutting, dutch angles, and catchy Bollywood music, reveals itself to be rather thin and uninteresting. He meets her once, he falls in love and will scour all of Mumbai to be reunited! Jamal's fortune, too, arises not out of his own cunning, but out of luck. Or is it fate? Luck? No, it's fate. The movie makes sure of that. The notion of destiny rarely interests me, because it takes free will out of the equation. If we are not acting of our own free will, then what's the point? Boring.

Far more interesting a character (disappointingly underdeveloped, then completely forgotten about by the end) is Jamal's brother, Salim. Had the film focused more on him than the weak storyline of Jamal and Latika, I might hold it in higher regard. That and getting rid of the Who Wants to be a Millionaire? segments, which take up maybe half the movie and amount to little more than a gimmick to put into posters. What seems like an arena ripe for social commentary amounts to little more than a waste of space and loss of time that could've been used to develop characters. The problem with Slumdog Millionaire, I think, is that it is messy. It tries to have its cake and eat it too, and the result is a half-baked romance and a half-baked indictment of western culture.

What Sin Nombre has, and what I feel Slumdog Millionaire lacked, is a sense of focus and restraint. Sin Nombre divorced itself from any overt politics and chose instead to focus on the people themselves. Slumdog Millionaire wants to be a wonderful romance while simultaneously preaching the dangers of westernization, and the result is muddled.

I now open the floor to [constructive] criticism.

No comments:

Post a Comment