There may be spoilers.

Director: Werner Herzog

Narration: Werner Herzog

Featuring: Timothy Treadwell

Images from the 2005 Lions Gate release.

"It is so weird though, when it sinks in just how alone you are."

Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man is a film filled with such unspeakable wonderment and horror, and I almost hesitate to call it a Werner Herzog film. It really is the work of two filmmakers, both with the unnerving ability to simultaneously express the beauty and indifference of the natural world. While it may be Herzog who interprets the images, it is Timothy Treadwell's footage that serves as the crux for contemplating not only the dichotomies of civilization and wilderness, but also how inexplicably nature can seem tranquil, chaotic, beautiful and ugly, all at once.

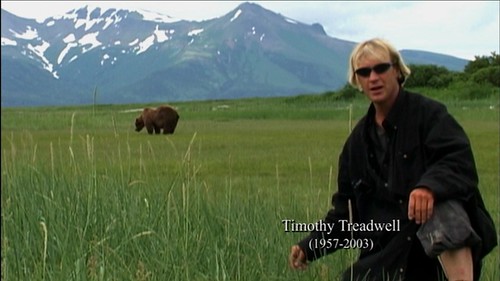

The film is a documentary chronicling the life of Timothy Treadwell, a man who, for 13 years, spent each summer living unprotected amongst wild Alaskan grizzly bears. In 2003, he was killed and eaten by a grizzly bear, along with his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard.

Grizzly Man contains images of such overwhelming beauty, that it becomes difficult to remember that these are unplanned events that have not occurred, for the most part, under the meticulous eye of a film director.

There is always a vulnerability associated with the freeness of the open space, and as Herzog observes, the Alaskan wilderness becomes a sanctuary as well as a confessional for Treadwell. It's as if his conviction is borne out of a hidden, cathartic urge that threatens to boil over if he were confined to civilization.

Timothy Treadwell is one of those rare individuals that skirts along the edge bordering society and nature, looking for order in the latter, while scorning it in the former. He is, in a way, a contradiction that wishes for an idealization that can never bear fruit. His self proclamation as "The Kind Warrior" reflects his own inner turmoil, and he seeks peace while filled with hate for civilization.

I think it would be too easy to label Treadwell as insane, and doing so would obscure the compassion and humanity in his convictions. In fact, I don't think I've seen very many people filled with as much compassion as Treadwell, and it irks me somewhat when I hear him being dismissed as a nutcase. Such is the case with Sam Egli, a helicopter pilot who helped transport Timothy's and Amie's remains.

He says that Treadwell got what he was asking for, and in terms of pragmatism, he is right. There is, however, this sense that rationality elevates and ennobles us to better people. A person like Timothy Treadwell, whose actions fly in the face of conventional common sense, is instantly scorned and shunned by society, who looks upon him with a smug sense of superiority. While I agree that Treadwell was indeed risking his life, I must respect his choice, since he lived amongst grizzly bears because he cared enough about them. I may disagree with his environmental practices, but I must acknowledge that his intentions were good. Compassion is something I feel is getting more and more difficult to find, and while my logistics may agree with Sam, I feel as if there is a certain satisfaction in his opinion of Treadwell that seems full of contempt.

I don't think a dispassionate speaker is a dispassionate person per se, it's just that film watching has conditioned us into believing that more melodramatic accounts of death are more realistic. To me, what fictional films capture is not the external reality, but the inner truth of emotions displayed expressionistically.

Willy Fulton (Timothy Treadwell's pilot), for instance, doesn't carry the same air of theatricality that the coroner does in recounting the events of Timothy's and Amie's deaths. There is the sense of quiet contemplation, and this seems to be more in tune with what we would see in reality.

The coroner's narration is less muted than Willy Fulton's, and I can't help but notice that he witnessed Timothy's death through the audio portion of the video tape. Perhaps it goes back to Herzog speaking of the "inexplicable magic about cinema," which amplifies an emotional response.

I often think about death, and films that explore this issue are particularly interesting to me. When I see Grizzly Man, I am invariably struck by the reality of it. It takes some reminding that Treadwell was a real person and not a persona, and there is something about the film that is incredibly subdued. There are none of the melodramatic cues of a conventional story or graphic recreations of horrific events (although there are brief snapshots), yet it is one of the most horrifying films I've seen. Not in the way of The Silence of the Lambs, but rather a shocking realization that I am watching footage of a man who will be dead.

There is the moment when Herzog listens to the actual audio recording of Treadwell's death, fortunately not exploited.

I often wonder what's more potent, a dramatized version of a death, or a record of an actual death. For instance, I wonder what the footage of Steve Irwin's death is like, as well as the audio of Timothy Treadwell's camera, and if they contain the inexplicable magic Herzog speaks of. Personally, I don't think it's possible to say one is a better representation of death more than the other, because in spite of the similarities in subject matter, they are really two completely different things.

With a fictional death, I think various aspects are dramatized and amplified, which leads me to believe that much of cinema is expressionistic. When I think about a real death, I see it as something much more introverted.

I think Timothy Treadwell was a man who stood at the great divide of civilization and wilderness, and could not, in the end, adapt to either one. I see the film in part as a contemplation on the extremes, as well as the middle. For instance, Herzog sees nature as something that is vile and base, and full of fornication, whereas Treadwell sees it in a much more harmonious and compassionate light. There are the instances of him mourning the death that must invariably come to all creatures.

While I do share Herzog's sentiments, I can also understand Treadwell's concern and distress over protecting wilderness. Yet my own opinions do not lie at either extreme, but in the middle. I see nature as something that is both wild and ugly, yet tranquil and beautiful. It is the yin and yang that the film explores, which is why I hesitate to call it a Werner Herzog film. That is, while Herzog may be the director, I do not see it as a film built upon his agenda. Treadwell's monologues serve to counterbalance Herzog's narration.

The most intriguing aspect of the film is Treadwell's footage, and the way it conveys not only Treadwell the person, but also Treadwell the filmmaker.

It's easy to see what interested Herzog. Here is a subject that not only stands upon the edge of society, but also a man who produces miraculous images.

I find myself hesitating to analyze a documentary from a filmic perspective, in part because it tends not to carry the same sense of craft that a fictionalized film does. There is, however, a narrative buried beneath the subject matter. The film serves as a sort of posthumous autobiography, through which we are revealed insights into Treadwell.

I must emphasize the notion that Treadwell is a contradiction, a man who could not bear society, yet could not cope with nature's overwhelming indifference. He was a man who wanted to live in an idealized and romantic world that erased the line between civilization and nature. He was a man who forged the persona of a lone sentinel, yet he was also a victim of that loneliness and yearned for friendship wherever he could seek it, even if it be with a wild fox.

While I think Treadwell planned quite a few of his shots into a narrative, I think some of the best ones are among the most spontaneous and unaware. There are the segments where Treadwell plays with his fox friends, and they seem to garner a supernatural meaning. When he is running with the foxes amidst a vast plain, there is a joy and freedom in the camera movement. And then, when he is chasing a fox that stole his hat, there is a frustration and angst that stems from his inability to fully reject civilized materialism.

Another sequence that I like a lot is when Treadwell is in his tent cursing the gods because it has not rained. Through his tirades, there is something likable about him, and while I do not admire his actions, I do admire his spirit.

This is a remarkable shot, both beautifully composed and full of meaning. Timothy is a man caught between two worlds, and his inability to have one without the other rends him in turmoil.

There is a poeticism to his speech that I don't think he was fully aware of. Watching and listening to him, we can see his insecurity, both through his filmmaking as well as his rants. He often repeats a phrase, as he repeats a take, as if to further reinforce the cohesiveness he thinks he sees in nature.

As he speaks about his past, he talks of his drinking:

"I drank to the point where I was going to die from it... or break free from it."

There is something about him that is tranquil, yet violent. I feel his angst stems from both his hate of society, as well as his unfailing ability to see the beauty of the wild, while rejecting its savagery.

These moments of anger set against backdrops of grandeur and tranquility are disquieting. Timothy Treadwell was a man of highs and lows and could not accept the middle ground, which hearkens back to the old tale of Daedalus and Icarus. His voice has such a gentle, child-like playfulness that it comes as a shock to listen to his violent ranting.

No matter how strange Timothy Treadwell may seem, we mustn't forget the most basic fact about Grizzly Man: he is dead. It is a film borne out of his death, and serves as an elegy of sorts, as well as a contemplation on life and death, nature and civilization, and chaos and tranquility.

The film also conveys the power of the camera, and its ability to capture seemingly unplanned moments that are filled with meaning.

Timothy Treadwell was clearly an unstable individual. But to dismiss him as that alone is to obscure his humanity. He seems to be filled with such emotion that he often just stops dead in his speech, incapable of expressing the flood of anger, sadness, and elatedness in what he considered his home. There is so much turmoil in his character that watching him becomes frightening. Not because of his insanity, so much as a fear for him.

I can't help be see similarities in Grizzly Man to that of the western. There is something about Timothy Treadwell's idealizations and his inability to cope with nature's hositility that are not too far off from the simultaneous beauty and harshness of the west. Like the outlaws in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West, he is just that: outside the law. Yet while he rejected the conventions of civilization, it seems he did not want to abolish them so much as take the best parts of them (compassion and friendship) and introduce them to a world of immense physical beauty.

I do not agree with Treadwell's environmental practices, but as I've stated before, I admire his spirit and I can understand his anguish. There is such an attraction about the real wilderness, and unfortunately, these areas are being colonized and exploited for tourism. They are the last frontiers and Timothy Treadwell was a man who needed to be along that razor's edge.