Spoilers galore.

Director: Jacques Tourneur

Screenplay: DeWitt Bodeen

Starring: Simone Simon, Kenth Smith, Tom Conway, Jane Randolph, and Jack Holt.

Images from the 2005 WHV Val Lewton Horror Collection.

This essay is somewhat influenced by feminist film theory, so it may help to be familiar with Laura Mulvey's "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema."

The Val Lewton pictures, however, do scare me and are unfettered by excessive makeup or cheesy special effects. I find Cat People scary, yet my purpose here is not to examine that terror. Cat People is terrifying to me and that’s all I have to say about that. But the movie provides us with a ripe opportunity to discuss feminist film theory and serves simultaneously as an indictment and affirmation of patriarchal society. Simone Simon’s Irena is the antithesis of the archetypal female role and her death affirms patriarchal dominance.

Feminist film theory holds that the cinema is reflective of the society that made it. You look at movies throughout history and the mainstream ones in particular place the female in the passive role of spectacle. She is more an object to be gazed upon than an individual with independence. As Laura Mulvey put it, she “is bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.” You can even go back to stories long before the advent of movies. Fairy tales like "Rapunzel" or "Sleeping Beauty" often have princesses trapped in towers that need to be saved by a valiant prince. There are exceptions, but the following tend to be the dominant gender roles thoughout history:

- Males are active and looking

- Females are passive and looked at

Even today’s blockbuster’s do this. Michael Bay (bless him) has perhaps two of the best examples of the 90s. Armageddon and The Rock feature men duking it out to save the day while women must sit back passively like good little daughters and housewives. Even now, in 2010, the old gender roles are still prevalent. Sherlock Holmes has the undeniably, effortlessly cute Rachel McAdams play the role of Irene Adler. That she’s easy on the eyes is an understatement… but the movie’s problem lies in placing her in the “damsel in distress” archetype (especially for a woman as intelligent and proactive as Irene Adler). Movies like Sherlock Holmes, The Rock, and Armageddon simply perpetuate an old-fashioned, patriarch-only dogma.

Cat People understands these gender roles and uses Irena as an outsider to patriarchal conformity. What’s immediately apparent when she first speaks is: she’s a foreigner. She’s an outsider to the US and more specifically, the patriarchal society. Oliver finds it strange they haven’t even kissed because it is conventional to the male dominated United States, as well as Hollywood. Her resistance to sexuality is a resistance to traditional female roles. When Dr. Judd kisses her, her subconscious sees that as a threat and her resistance manifests itself in transformation to a panther.

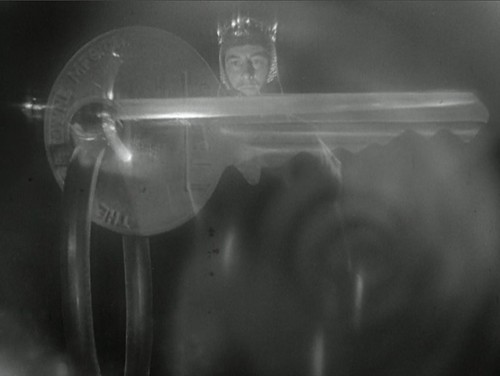

You can trace this fear of male dominance back to King John of Serbia liberating his country from the Cat People. Look at the statue in Irena’s apartment. It is King John riding his horse and brandishing his sword with a cat skewered by it. Irena is connected to the cat by her ancestry; she believes she’s a Cat Person. Simone Simon’s face even looks like an innocent kitten. That, and she’s greeted by a Serbian woman described as cat-like. More specifically, the cat is emblematic of the wild, carnal female untamed and unfettered by male dominance. King John, however, has slain this image with his sword, a classic representation of male power. That Irena keeps such a statue in her house is a sign that she has left one patriarchal society and arrived at another. She has the statue not of her own free will but because Serbian society and King John tell her to.

There are several key sequences that inform us about Irena’s defiance of the male-dominant society, whether she’s conscious of it or not. As I’ve already mentioned, she’s resistant to “kissing,” and in Code-era Hollywood of the 1940s, the kiss could (and often did) represent consummation. Irena’s reluctance to even kiss Oliver (which she attributes to the curse of the Cat People) is a refusal to accept the female’s traditional sexual role. The second reason for her defiance lies in her almost male-like possessiveness of Oliver. When she sees Alice with Oliver, she doesn’t simply become jealous; she transforms into an incensed and aggressive panther. It’s as if Irena and Oliver are switching gender roles, and her transformation is not dissimilar to various testosterone-laden (male) beasts like King Kong, Frankenstein, or The Beast in Beauty and the Beast.

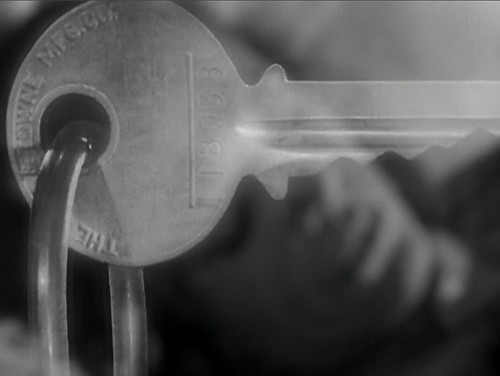

I think the moment she subconsciously accepts her defiance of patriarchal society is during the dream sequence. Remember she had just undergone her first transformation, stalked Alice, and ended up slaughtering a few lambs at the zoo. As she’s dreaming, we see cartoon cats approaching the screen, King John with his sword, and then the zookeeper’s key superimposed on the sword. The key is phallic, but it’s also a symbol of control. When she takes the key, she’s symbollically embracing her defiance of the patriarch and she’s also gaining control over her own life. Dr. Judd may be the one to wound her, but she ultimately chooses to open the cage and be killed by the panther.

Irena’s choices, thoughts, and character make her a diametric opposite of Alice. For a while, Irena genuinely wants to start over, be a good housewife, cook dinner, and greet Oliver when he comes home from work. But he tells her it’s “too late,” which is just as well. He’s fallen for Alice, who can probably play the role of housewife splendidly. With Irena, Oliver can never be sure if she’s really changed. It probably helps that Alice has a good old-fashioned American accent and accepts her traditional female role from the get-go. When panther-Irena threatens them at work, it is Oliver protecting Alice, as it should be. He even uses a gigantic T-square to fend her off. The instrument is obviously a cross, and patriarchal society along with the church supports the long standing tradition of male protecting female.

Irena is a threat to the gender norms, so society gives her a choice: assimilate or be destroyed. She can’t do the former, so her death is necessary and symbolic of male dominance quashing a female who, by her very nature, attempted to defy the rules of society. Cat People conveys this through its mise en scene as well as its narrative. Whether it is more an indictment or affirmation of patriarchal society is up for debate, but it is aware of both stances, which is more than we can say for various male-centric movies like Spartacus, Seven Samurai, The Rock, or The Searchers.

One of the strengths of Cat People lies in its refusal to villain-ize or simplify Irena. It would be too easy to brand her as the "bad guy" when she's anything but. She gains our sympathy through her quandary and we are allowed to see her when she's at her most vulnerable. She's a movie "monster" with humanity, suffering the same loneliness that overcomes so many outsiders. This is something Dracula never understood, and instead of gaining our sympathies or complicating our notion of a villain, the picture is content to have Count Dracula stare in the camera like Zoolander (come to think of it, Stiller was probably influenced by Lugosi).

No comments:

Post a Comment