There may be spoilers.

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto, Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Starring: Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura.

Images from the 2002 Criterion Collection Release.

The film begins under a torrential rainstorm, and an old man and a priest huddle under the ruins of Rashomon temple. They recount the story of a man's murder and his wife's rape by the infamous bandit Tajomaru as a commoner listens on. Each perspective clashes with the other, leading to one of the most thought provoking stories on the nature of truth ever told.

I think the visuals of Rashomon are among the most striking I've seen. The Criterion disc comes with a feature on cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, and while at first, I thought it odd to have that feature as opposed to one on Kurosawa, I began to realize the importance of cinematography in grasping the realistic feel of Rashomon.

Rashomon gives us contrasting scenes that are almost like mirrors of one another. Consider: The scenes at the temple feel like they exist in a place isolated from the world. Likewise, the scenes of the murder in the forest feel isolated. Yet the visuals of each place are completely opposite. The temple scenes are composed of the straight lines of the temple, the sheets of rain, and the light is softened by the rain. The forest scenes on the other hand, have a hardened light and the shadows form messes of dappled light. Both atmospheres feel real, yet isolated. It's imperative that the film feels realistic.

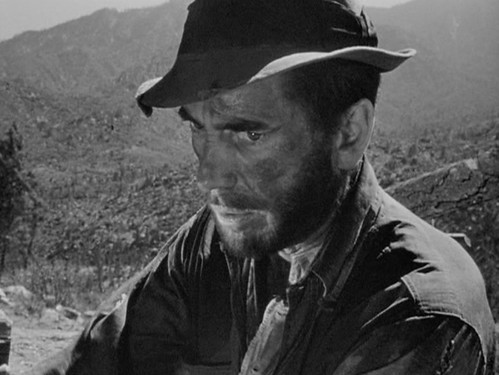

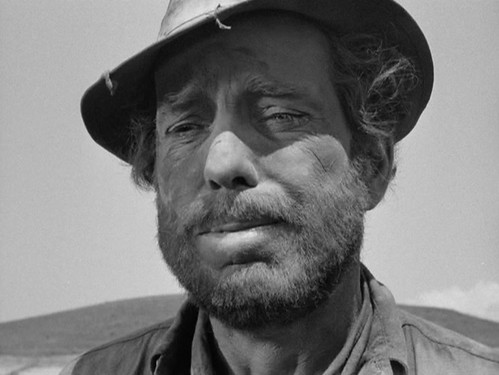

As the old man recounts his finding of the dead body, we are given a long transition in which we see him walking and walking and walking...

When I first saw this, I was wondering why on earth this was going on so long, but as I watched the film more, I began to realize how necessary it is. This is the setup that will shape the feeling of reality throughout the film. We can see the hard sunlight and dappled shadows on his face. The camera shows the old man from just about every angle and every length of shot. One tracking shot shows him in a long shot and as he walks, we go to a closeup and the camera encompasses his movement. This is a subtle way of reminding us that the camera sees everything.

I found the scenes in the forest to be very visually brutal. The lighting feels harsh and unfriendly and the setting is so chaotic when compared to the calm and peaceful white noise of the temple. I think the forest scenes can be an allegory for the horrors of humanity, whereas the temple scenes are representative of the good in humanity, like a sanctuary blanketed from reality. The length of this sequence (for me) also adds to the suspense and believability of finding the dead man, which is absolute stylized acting on Takashi Shimura's part:

Speaking of stylized acting, I know that Kurosawa's 50s & 60s work does have much "overacting." Especially with his number one, Toshiro Mifune. I think with Rashomon in particular, the stylized acting is a necessity. Whenever we are told a different perspective and shown it, the characters suddenly shift personas, because even though we, the audience, see these events objectively, the camera is still subjective. For example, as Tajomaru recounts his version:

The music is very heroic, yet at the same time, parodic. When he says he stole the horse from the dead man, we see a flashback of him riding heroically in the distance, the music striking up gallant chords:

In the film, Toshiro Mifune is very animal-like. When he's sleeping he's like a lion. When he's awake, I'm reminded more of a monkey.

Consider the rape: In Tajomaru's mind, there never was a rape because he believes the wife complied to his advances. The brilliance of Rashomon is that it is so visual. We don't just hear each person's testimony, we see it. We see the simple action of a knife plunging into the earth, a phallic symbol if I ever saw one:

I don't believe that the versions of the story told by Tajomaru, the wife, or the dead man are fabricated lies. I think these people honestly feel that's what happened. They have subconsciously tricked themselves into believing their version of events is true. In Tajomaru's case, his character is shown with a bravado that is lacking in other versions.

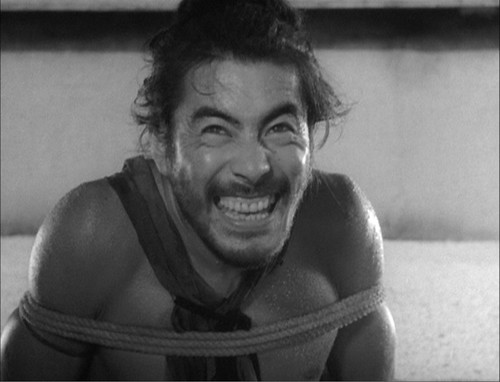

Here, Tajomaru has just tied up the man, showing his machismo and elatedness in subduing him:

Kurosawa evidently made Rashomon with the fundamentals of silent film in mind. The music playing here reminds me of those old silent cartoons where the villain has just tied up the damsel in distress to the railroad tracks and the hero must come to the rescue (only here, the husband and wife are reversed).

Contrast Tajomaru's behavior above with the old man's version of the story, where the wife chides both men as weak for not wanting to kill one another over her, and we see Tajomaru looking more like a timid schoolboy:

We also get the same contrast in perspective in viewing the two fight sequences. In Tajomaru's version, both men fought like seasoned warriors, clashing swords in a heroic chambara style:

Contrast this with the old man's version of the fight, where the two men can barely even hang onto their swords (ha! impotence...) and resort to lots of crawling on the forest floor, scrambling for some clumsy advantage. This scene is actually quite funny, and I'm not sure if this is what actually happened, or whether the old man just remembers it this way (as with everything else in the film). It's possible his perspective is biased to his age in viewing these younger men.

We see this contrast with all the characters. The wife, for instance, either truly believes in her victimization or is simply a really good actress:

Her own version emphasizes her as the victim, even more than her dead husband, who she claims gave her a glare so scathing, she was begging for death:

Again, her character is completely opposite to everyone else's version, in which she instigates/begs for the two men to kill one another to win her.

I think the husband's version is essential to the film for at least two reasons. First, he is portrayed as the victim having lost his wife (who begs Tajomaru to kill him) and his masculinity, having been tied to a tree stump. Second, he commits seppuku, as a point of regaining honor. It is a paramount message in Rashomon that in the first three versions of the story, the narrator is the one who kills the man. I'm not an expert on Japanese culture, but looking at the film on its own, Kurosawa seems to be commenting on the idea of honor, and why killing (even oneself) is considered such an honorable thing.

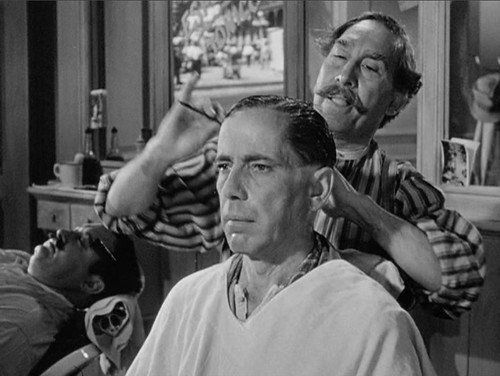

The fact that the husband's version is told through a medium is bound to have skeptics. I, for one, don't believe in the afterlife, but I feel the husband's version is necessary to give the film its symmetrical, mirror-like structure. The scenes with the medium are some of my favorite (even though I don't fully comprehend them) for their haunting beauty:

I think it's worthwhile to point out the symmetry of Rashomon and how it's very much like a mirror halfway through. First, we are given Tajomaru's version of the murder, in which the man is killed by Tajomaru with a sword. In the wife's version, she believes she killed him with a dagger (at the very least, she passed out, woke up, and saw a dagger in her husband). The husband's version has him commiting seppuku with the dagger. I believe that the husband's and wife's versions of his death could have occurred at the same time. He could have killed himself, and when his wife came to, she may have surmised that she did the killing. Of course, in the husband's version, he dies alone, as the wife has run away. Then again, the whole film questions the reliability of a person to recount events exactly as they occurred, and given the mental states of the husband and wife, the truth could be a mixture of their two stories. The final version (of the old man) again has Tajomaru killing the man. In the old man's version, there is none of the heroism in Tajomaru's. There is a symmetry among the four versions and they almost form a sort of mirror image of each other.

In the commentary on the Criterion disc, Donald Richie says the film has a lot of sharp edits and virtually no dissolves through the first 80 minutes. This is Kurosawa's comment on cinema itself. Edits constitute a form of lying, because they involve unnaturally juxtaposing two separate pieces in an effort to make them cohesive (i.e., the story's cohesiveness depends on fragmentation). The sharp edits and the horizontal wipes are very clear cut and distinct. This can be seen as the disconnect in the world today, as people alienate themselves and lie to others. Towards the end, however, Kurosawa offers us a small glimmer of hope... humanity may yet survive the mess they live in, and meld and mesh together in a way for the betterment of mankind: