Wartime Romanticism is common enough, especially in the movies, but no picture does it quite like A Canterbury Tale. Films like Casablanca and the Archers' own A Matter of Life and Death are achingly romantic, yet their love stories are the offspring of war itself; you could argue that stories of their ilk—frequently an American falling in love with a European—romanticize war conditions. Casablanca does this in particular, and while a beautifully crafted movie, rings of extremely lofty ideals as well—namely sacrificing one's own happiness for the greater good. Its characters are admirably noble, but this self-sacrifice can arguably be seen as the film inadvertently advocating a more utilitarian, even nationalistic, vision.

A Canterbury Tale, on the other hand, is defiantly Romantic in a more traditional sense—or rather, its Romanticism isn't mired in glorifying militant nationalism. It is the individual and individualistic values that matter most here. The movie doesn't overpower you with its sense of spirit—at least not so forcefully—but adopts a leisurely pace seemingly unconcerned with the war at all. Yet its subdued rhythm and extremely casual nature are essential to its antiwar sentiment. Most war movies tend to romanticize war or display the horrors of it, yet they're inevitably mired in it; all they can see is war.

A Canterbury Tale, on the other hand, hardly seems informed by war at all. It doesn't ignore the wartime environment, it's just not seen as a constant threat. Here instead is a movie that focuses on what we have, not what we've lost—proudly displaying a strong, proud sense of cultural heritage. It begins with shots from the 14th Century, its pilgrims bathed in light, when nationalism and industrialization hadn't yet taken root. Powell and Pressburger transition us beautifully to modern times, match-cutting a falcon to a bomber flying towards us. The narrative tone shifts from historical reverence to a more imposing, threatening atmosphere—wartime. In place of happy peasants and falcons are tanks and bombers.

Yet it isn't the military-porn of Triumph of the Will; images showcasing the instruments of war are fleeting and the movie quickly segues into its characters. The way A Canterbury Tale introduces us to its three modern day pilgrims is interesting. Indeed, we hardly get a good look at them because of the blackout, which would seem a deliberate contrast to the ancestral pilgrims basking in daylight. It's as if the Archers are suggesting we've changed—like we've lost our innocence and are living in an age of pessimism. The narrator even seems to lead us in this direction and shifts to a more imposing tone when we see the tanks:

Though so little's changed since Chaucer's day,

Another kind of pilgrim walks the way,

we modern pilgrims see no journey's end...

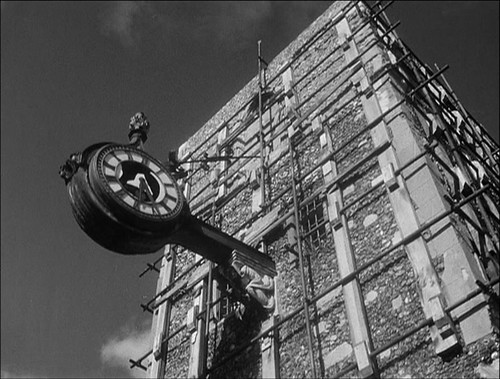

Yet the Archers aren't interested in augmenting the already heightened modern pessimism of its wartime audience; they are trying to subvert it. The sense of impending doom quickly dissolves, along with wartime threats, into the quaint, cozy adventures of our plainspoken heroes. Powell and Pressburger seem intent on defusing our fears of the war by reminding us, quite simply, that life goes on, same as it always has. Look at this shot:

Hardly seems to belong to the WWII climate or even an industrialized world at all. This scene at the farm is filled with possibly the most casual, understated antiwar sentiment ever captured on film. Sgt. Bob Johnson's conversation with the farmer about lumber reveals a fraternal camaraderie that subverts any nationalist tendencies. The scene envisions people as people, not as American and English. The world Powell and Pressburger have captured here also hearkens to a simpler, pre-industrial age. As Bob so eloquently puts it: "You can't hurry an elm."

There's this lovely exchange as well:

Farmer: We get all our local news at 6 o'clock, Miss.

Bob: You got a local newspaper?

Farmer: That's when the pub opens!

Yes, even the newspaper's gone in this town, further removing it from modernity.

A Canterbury Tale is filled with scenes like this—overflowing, even—and it's all thanks to the script penned by Pressburger. Over and over we're reminded the importance of a good script, by Hitchcock, Kurosawa, etc., yet we seem to ignore this in favor of the director. If you don't believe me, try naming as many directors as you can, then try naming as many screenwriters. Powell and Pressburger were on to something, sharing the credit as authors of the picture, because a movie needs both. A Canterbury Tale's writing is its blood; it's what gives it life and a heartbeat. There are so many brilliant little moments like the one at the farm I'm hesitant to go on for fear of spoiling the experience. This movie breathes its own special brand of antiwar sentiment that's difficult to find comparisons to.

Nationalism and Industrialization are widely seen as twin catalysts for both World Wars, and A Canterbury Tale achieves its antiwar sentiment in attacking them, frequently through its brilliant exchanges of dialogue. Although maybe "attack" isn't the right word. Paths of Glory or The Americanization of Emily attack. A Canterbury Tale's attacks are more like casual, almost playful jibes. Like Alison's exchange with the barkeeper:

Barkeep: do you know the lord mayor of London?

Alison [jovially]: I don't.

She's hardly ashamed of her lack of nationalistic ethos. And neither is Bob, on the glue-man:

Bob: Say, this guy might dangerous. Have you got a gun?

Policeman: This is Chillingbourne, Sergeant Johnson. Not Chicago.

Bob: Say what kind of a crack is that? I'm from Oregon.

This scene isn't merely another jab at the supposed need for national pride, but also a reminder of how the us-and-them mentality imbued by nationalism has distanced us. And the whole glue-man subplot—played with the exigency of a Scooby-Doo episode—is a delightfully subversive affair. Wartime stories like the film noirs of the day had the cloud of war over their heads, even if they weren't explicitly about it; they were filled with intense, serious dramas involving murder and loss of innocence. Yet the glue-man episode feels like a deliberate affront to this wartime sobriety and satirizes it with Colpeper's misguided sense of civic duty.

Yet even Colpeper isn't reduced to some freak-show parody and seeing Alison walk by his statuesque form unnoticed, at the end, is very poignant. The extraordinary thing about A Canterbury Tale is it doesn't stack the deck; it remains uncommonly humanist. Remember those instruments of war? Well, tanks here are simply vehicles used to get around in and ask pretty girls on dates with. The military can't homogenize our humanity into some faceless killing machine, the Archers are saying. That scene—defusing the military by subverting a tank's usual purpose—is the Archers' equivalent of planting a daisy in a rifle barrel. Or, as another farmhand tells Alison: "What makes a civilian into a soldier? The uniform." Indeed, the only "active duty" troops are children:

Above all, the film humanizes the individual. There are so many opinions flying about in this movie; it's filled with all manner of civilized argument that snubs a homogenous national identity where all its citizens talk, walk and think the same. It's a movie that basks in freedom of thought. Yet it would be wrong to call A Canterbury Tale naive or too idealistic, I think. It's simply embracing what we've already had and affirming our sense of personal purpose. It's hardly ignorant of the war, either. The power of its most sober images lies in their ultimately optimistic lining. Amongst the bombed ruins of Canterbury, we see little signs popping up like seedlings, reassuring us that while the buildings may be crushed, the town's will is not.

A Canterbury Tale is arguably my favorite Archer movie, although it's kind of pointless comparing it to Black Narcissus. It's an argument for individual triumph over militant nationalism, yet it doesn't feel like a movie sparring for a fight. It's a humble criticism of war, in deliberate contrast to the fangs of Paths of Glory, Army of Shadows, or The Americanization of Emily. I hold it up largely because its humanist angle swells with gentle emotion. It's mystical in its approach.

No comments:

Post a Comment