Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Smiles of a Summer Night (1955)

Monday, June 14, 2010

Decalogue IV (1988)

Pauline Kael—who I’m apparently apt to quote—said that we shouldn’t view movies in a vacuum. When we see a movie, we should bring all our experiences and everything we’ve seen, read, or heard into the theater. The way we perceive one movie can inform us of how or why another one works so well, just as drawing on our own experiences can. I’ve been kind of slow to write about Decalogue IV, but I think I’m finally ready to do it, in part because of a short story I read by Raymond Carver. The story is “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” from the collection Short Cuts.

So what on earth does an American short story with no religious connotations have to do with a Polish television series based on the Ten Commandments? For me, a lot. What fascinates me about Decalogue IV is not its connection to the 4th Commandment so much as its depiction of a relationship changed by discovery. It’s not preaching or attacking the 4th Commandment, nor is it bringing it to the forefront. Rather, the Commandment can be considered in the context of the story; it can be considered in the drama and the situation the characters are in. This is one of the series’ greatest strengths; the Commandments are hardly depicted literally and the whole point of the movies isn’t reduced to some contrived fable tied down to them. Decalogue is about the people that populate its narrative, in a way that is not at all dissimilar to Short Cuts.

In “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” we see a happily married couple dredge up an incident three years ago where the husband, Ralph, suspected the wife, Marian, of cheating on him at a party one night. While Ralph has always inferred there was an affair, he has never known for sure. The doubt that existed was insular, and effectively buried the incident under a veneer of tranquility. But that peace is more a prison than anything else; a stasis that traps Ralph and Marian in a quiet frustration that is itching to bubble to the surface. Their situation is like a family of a missing person who is suspected to be dead but is never found. This eats at the mind, to the point that you’ll do anything to discover—or reveal—the truth.

In Ralph and Marian’s case, either their lack or harboring of the truth provides the impetus for catharsis; they need some way of releasing their frustrations. The great thing about Carver’s story is that it doesn’t offer some pat conclusion to such a weighty dilemma, because any such solution would invariably feel contrived and simplistic. The story simply marks the crossroads that countless people have found themselves at throughout their lives. Carver suggests such a catharsis can be therapeutic, but doesn’t endorse it as some kind of magic solution. This is all conveyed subtlely, through actions that are realistic, not melodramatic:

“He tensed at her fingers, and then he let go a little. It was easier to let go a little.”

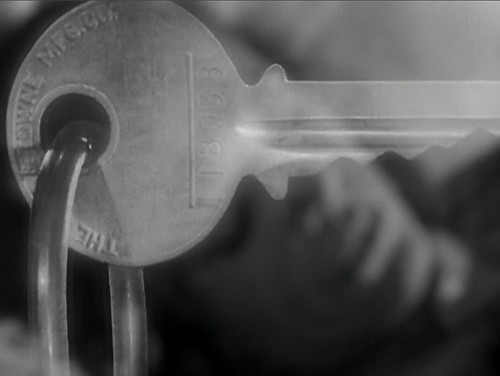

“Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” carries a strong similarity to Decalogue IV, not only in content—uncovering a secret that has been waiting to be discovered—but in the catharsis a discovery produces. Decalogue IV, too, has a secret that’s been harbored by the father, Michal, from his daughter, Anka. This secret is in the form of a letter Anka’s mother wrote shortly before she died. Michal keeps this letter in an envelope marked “To be opened after my death.” Anka knows of this letter and when Michal goes on a business trip and leaves it behind, she decides to open it.

She finds a secluded spot by a lake and carefully cuts the envelope open with scissors, only to discover another envelope inside marked “To my daughter, Anka.” As she’s about to open it, a man walks near her carrying a canoe over his head. The man causes her to reconsider and it is here that we find the movie at its most poetic and conscious of its religious theme. It is such a classically Kieslowskian moment, to have a complete stranger inadvertently give Anka pause. Who this man is and what he thinks hardly matters, and while it’s possible to see him as some sort of surrogate God judging her, such an interpretation is beside the point.

What matters is the moment provides a break that causes Anka to reevaluate her actions. Whether or not she’s considering the 4th Commandment, she refrains out of respect and love for her father. As soon as she opens the first envelope, she can tell her father didn’t write the second; how could she if the writing is clearly different? “To my daughter, Anka” must’ve been written by her mother. Like Ralph in “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?,” Anka can pretty much guess at the letter’s contents. We know that Anka is no idiot anyway—her physical examiner tests both her eyesight and intelligence by spelling “father” in English with the eye chart letters and, not being able to see well, Anka guesses the smallest letters. But rather than simply affirm her suspicions by reading her mother’s letter, she instead forges another in her mother’s hand, using this one to confront Michal.

I don’t think trying to explain why she chose this route is the best use of our time, simply because she becomes a psychiatric case study for us to scrutinize. Our explanation might make sense, just as the psychiatrist’s does at the end of Psycho, but it too will invariably come across as sobering, contrived, and silly. Robert Altman writes of Raymond Carver:

“[…] what he really did was capture the wonderful idiosyncrasies of human behavior, the idiosyncrasies that exist amid the randomness of life’s experiences.”

You could say the same thing of Kieslowski. His movies, so often filled with random or tangential moments, flow with the spontaneity and artistic license we associate more with music than with movies. These moments are almost never rationalized and why should they be? Not only should movies allow the audience to suspend their disbelief, but irrationality is something that informs the human experience. We always seem to try and explain why every single thing happens in movies and criticize the irrational, but maybe we ought to take a look at ourselves first. No doubt we’ve done countless oddball actions that we fail to rationalize. Every little action in a movie, too, needn’t be examined with a fine tooth comb.

What is important and what should be discussed is the cathartic ramifications of Anka and Michal’s actions. For Michal, he’s been harboring this letter for years and years and while he doesn’t know the contents, he can pretty much infer that he’s not Anka’s biological father. Michal is informed by dialogue like “I don’t know.” He’s plagued by uncertainty, and his plans to give Anka the letter failed to pan out; she was either too young or too old. Yet the urge to reveal whatever is in the letter—and be honest with his daughter—finally causes him to leave the letter for her to open. He is a dam, overburdened with secrets and yearning to burst in catharsis.

His passive method of basically baiting Anka with the letter reveals the fear and anxiety he has with confrontation. Anka says: “You want things to happen without being involved.” Indeed, this is true of many of us. Reality is often too frightening to face, so we instead hide behind letters, email, texting, phone calls; sometimes we’ll simply bury ourselves, taking refuge in a book, games, or a movie in hopes that what we’ve done will take care of itself. But we can’t shun reality, and our vacillations and refuges only exacerbate the problem. “Out of sight, out of mind” only makes sense in the moment, and doesn’t provide us with any lasting comfort; it is only a temporary reprieve.

Both Anka and Michal are living a lie by not discussing what they know to be true. Their conversation reveals the change in their relationship; it’s no longer as simple as the father-daughter dyad. The complexity is that Michal sees Anka not just as a daughter but as a woman as well. She sees him not simply as a father but as a man. He does feel jealousy when she sleeps with men and she does feel unfaithful. It’s hard to say whether they’ve always felt that way or whether they are simply reinterpreting their feelings in the context of discovering the truth. For me, it's the latter; our interpretation of feelings isn't concrete and something like jealousy can be transmuted from something more universal like the need to protect. After all, fathers are bound to be protective of their daughters; it’s just the way things are. Michal could simply be considering that paternal instinct in light of discovering he's not Anka's father.

Confrontation is neither destruction nor reparation; it’s a precursor for either one. When Anka discovers Michal doesn’t merely think of her as a daughter, she undresses and offers to sleep with him. It’s such a raw and vulnerable scene, one that she does out of frustration; we almost hold our breath at such a tense moment, knowing that one action could be irreversibly damaging to their relationship. Michal values that too much, however, choosing to paternally cover and embrace her. Such moments are extremely risky, but Kieslowski pulls it off beautifully, in part because he never loses sight of the character’s humanity. The morning after, Anka wakes in panic, unable to find Michal and thinking he’s left for good. He hasn’t, and she sees him walking outside to get milk. Such a simplistic, everyday act tells us that reparations have already begun.

I’ve never regretted seeing a Kieslowski movie. The great thing about him is that, for all the intense emotional situations he creates, he’s never made an excessively bleak or exploitative picture *cough* White Ribbon *cough* Antichrist *cough*. He offers us hope in the face of tribulations that never lose their realistic weight. It’s a tight-wire balance that countless movies have fallen off of and in doing so, they’ve lost their dramatic relevance. The Decalogue is a wholly unique and special work precisely because it doesn’t force feed us an agenda. Rather, its themes are integrated in the realism of the story and the characters, who aren’t even characters so much as real people facing problems like anyone else.

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Slumdog Millionaire: Trash on a Pedestal

Slumdog Millionaire is cotton candy; it's junk food because it tastes good, but dissolves fast. Thematically and emotionally, it offers pseudo-profundities that only seem really deep. Its declarations of fate, for instance, are no deeper than those found in the ultra-consumerist anime Yu-gi-oh!. It provides us with nothing profound or troubling to think about, instead indulging the audience in what it wants to see, rather than what it ought to see. It is an instance of trash revered as art; audiences and critics fawn over it because they don’t know the difference—or because they can't find anything better. Slumdog Millionaire is no more artful than Armageddon, and the Bruce Willis picture is arguably a more genuine and honest work. The thing that irks me about Slumdog is its aspirations to be more than it is and the attention that’s lavished on it as if it’s a work of truth and brilliance. It is not art, it has nothing especially challenging or interesting to say, and frankly, it’s an emotional dud.

Slumdog is so dependent on its gimmick that if we were to remove it, we’d see how banal the movie really is. The Who Wants to be a Millionaire angle is little more than a novelty. The indictment of westernization is slight and innocuous; the let’s-see-how-he-knows-the-answer business is contrived and shallow. What’s more, that silly question at the beginning and the answer at the end merely make a gimmick out of the gimmick; it’s like a parody of parody. Such a juvenile declaration of fate deprives the audience of anything to think about. “It is written.” No questions, please.

Such a message not only has little basis in reality but flattens the characters in the story. Instead of representing real people with real thoughts, feelings, and aspirations, these characters become one dimensional pawns used by the movie to appeal to the mass audience and their wishes. The movie's been called a love story "above all" but does it even do a good job of that? We're frequently shown our star-crossed lovers Jamal and Latika separated or being separated by outside forces, so it’s no wonder we’re getting all anxious to see them [finally] be together. But they spend so much time apart, I begin wondering what Jamal even knows about Latika. In pretty much their only conversation, they dream about what they’ll be able to buy (“weddings, government things, big parties…Big money”). Their concerns are entirely juvenile and materialistic, but the real problem is they don’t grow up. Especially Jamal. I remember the inspector saying to him: “all you think about is money.” That, and Latika. So it’s money, money, Latika, money, and Latika.

Jamal is such a banal character that I wonder how people could take a liking to him. He’s not the one making things happen; things are happening around him and he either lucks out or not. That’s the whole premise of the movie and repeatedly Boyle provides us with imagery that shows Jamal as the helpless but spirited kid from Bombay. Early on, we see alternations between Jamal on the show with the Indian version of Luis Guzman and being tortured by the host’s private investigator. The torture scenes hold no power to shock us, just as the shaky camera and dutch angles galore don’t have the impact they should. This is because Boyle releases his tension in little bursts, thus desensitizing us with excess.

Rather than see a single spike of violence, we get it diffused across a scene; rather than a single, jarring cut to a dutch angle, Boyle cuts, cuts, and cuts from one dutch angle to another—I swear it’s like a seesaw. Such effects seem effective, but only intellectually so. This is the problem with the shot-by-shot analysis I’ve grown so weary of; it’s academically true, but we lose the flavor and feel of the picture when we start assigning meaning to individual shots and cuts. In other words, we think about what we should feel without actually feeling it. Boyle probably saw Do the Right Thing or The Third Man in film school and decided dutch angles would be good for chaos/change/character development/tension/emotion. The thing is, he uses it for every one of those things to the point where the shot no longer has the impact it once did. These effects would be forgivable if Jamal weren’t such a shallow, underdeveloped character.

The movie is so intent on dazzling the audience that our understanding of its characters suffers. What do we know about Jamal? Well, early on we see him incapacitated, with the interrogator stringing him up, slapping him around, and running electricity through his toes. Dev Patel excels at that I-just-got-slapped expression but it’s about the only one he can do. We then see a young Jamal about to catch a cricket ball but then getting blown over by an airplane’s gust. Such images peg him as powerless; he is subject to whatever fate the heavens have in store. “It is written” the movie concludes, but by whom? Is it God? Not likely, since the movie barely carries any religious weight to it. The only person actually seen praying is Salim, and he’s hardly given any sort of proper redemption. He dies in a bathtub full of money, having “redeemed” himself by helping Latika. Yet this final act—perhaps the only humanist one in the movie—is completely dropped by the end as Dev Patel and Freida Pinto lead into a Bollywood dance number.

It’s like the movie wants to show you terrible things, but then wants you to forget how badly they made you feel. Yes, the poor, poor [bourgeois] audience needs some consolation for the frightening realities they’ve just been exposed to, so here’s a Bollywood dance number. Salim, who is probably the most human and realistic character in the movie isn’t given the time he deserves. He’s Jamal’s brother, but his death is glossed over by 20 million ruppees, [finally] meeting at the train station, and breaking out into an exhuberant dance number. The movie wants to give its audience an endless respite from the horrors it shows, but it is so intent on—or maybe obligated to—showing those horrors in the first place. Everything it does is designed to defuse terrible realities. A child covered in shit isn’t meant to garner our sympathies but is there for comic relief. Indeed, the audience I saw it with roared with laughter at a young Jamal covered in excrement. The scene is as absurd as the Who Wants to be a Millionaire device and is pure novelty; it’s no more than exploitation.

That Slumdog has been showered with awards is a sign that Kael was right when she said: “When we championed trash culture, who knew it would become the only culture.” Slumdog Millionaire is little more than wish-fulfillment, but what makes it so detestable is it obviously aspires to something greater. It reminds me of that Simpsons episode where the producers of Itchy and Scratchy are trying to figure out what their audience wants: “So you want a realistic, down-to-earth show that’s completely off the wall and swarming with magic robots?” Slumdog wants to show awareness to the reality of slum life. It wants to be a compelling love story, it wants to make its audience happy but uncomfortable, and it wants to criticize westernization while embracing it all the same. It’s a movie that thrives in the politically correct milieu we have today and is just as wishy-washy. It ends up doing everything half-assed; it’s like the [often liberal] person who wants to be politically and globally “aware” and knowing, and achieves that by a skim of the newspaper headlines.

Much of my argument is dependent on how Slumdog Millionaire has been received, which is usually frowned upon. But to evaluate such a movie—which is so beloved by critics and audiences alike—in a vacuum forgoes one of the main functions of the movie medium. Perhaps more than any other, movies are a public medium. Public perception, while not everything, is integral to evaluating a movie; how a work is perceived indicates its merit. To simply blame the audience for misinterpretation precludes artists from reproach and rejects the responsibilities they have. In the end, however, it’s a two-way street. Audiences are to blame for idolizing and enjoying a movie that turns shit-covered children into a laughing stock, and the artists are to blame for feeding them such wishy-washy, pandering “art.”

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

Decalogue III (1988)

Director: Krzysztof Kieslowski

Screenplay: Krzysztof Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz

Starring: Daniel Olbrychski, Maria Pakulnis, and Joanna Szczepowska

Images from 2003 Facets release of The Decalogue.

On Christmas Eve, the air is charged with a sanctified air; the feeling that the day will be perfect and holy, or at least, the feeling that it ought to go that way. It's kind of like church: a special time and place where you stay indoors, spend time with your family, and avoid impure thoughts or actions. But the idea of the Sabbath—whether it be Saturdays, Sundays, Christmas, or Easter—is a human construct subject to human compulsions.

The sanctity of the day (or the place) is only as strong as we're willing to make it. In and of itself, it has no meaning. Decalogue III hardly endorses a strict interpretation of keeping the Sabbath holy. If anything, having Janusz spend Christmas Eve and Morning with his former lover Ewa proves more cathartic and redemptive than sinful. In this sense, it's iconoclastic of the 3rd Commandment.

By iconoclasm, I don't mean the Byzantine kind; Decalogue III's iconoclasm is more progressive than that. The old kind was where religious images were banned because they were an inaccurate representation of Christ; things like paintings or sculptures desecrated Christ's true image because they could only show his human likeness—any depiction of his divinity being impossible in a physical medium. The argument behind Byzantine iconoclasm was that depictions of a physical Christ were forms of pagan idol-worship. That is, the symbol itself was being worshipped and not what it represented or implied.

The problem with Byzantine iconoclasm is that it enforces a dogma that restricts our freedom of interpretation; forcing us into a singular way of understanding and respecting Christ's sacrifice. It grants no latitude for other sects and denies tolerance. This leads to another form of idol worship; the metaphysical image of Christ being such a holy one that it cannot even be represented physically, much less questioned. Any questioning or defiance of the decree is viewed as an act of blasphemy, and there is no leeway in understanding the offender's motivations or situation.

The rule being enforced—that Christ's image is so sacred as to be impossible to depict physically—is not unlike a strict adherence to the Commandments themselves. Such an interpretation—one that denies any good coming from defying the Commandments—forgoes one of Christ's most important teachings: forgiveness. Forgiveness, in my mind, is necessarily preceded by empathy and tolerance. Without these, how can we hope to forgive someone's actions? We may say we forgive them, but for us to mean it, isn't it necessary that we understand their feelings and motivations?

The Commandments can't be treated as the immovable object. We can't say: "uh-oh, you didn't keep the Sabbath holy. Blasphemy!" because it simplifies the human condition; it denies any possibility for exception even though we know the world can't simply be divided into good and evil—it's a big gray area. It is human to err. We must be willing to forgive mistakes and moreover, understand and empathize with them. This is where Decalogue III works so well: in subverting our preconception that Christmas Eve ought to be holy—that any defiance of this is sacrilege.

In the beginning, Janusz feels that no good can come from spending all Christmas Eve with Ewa, his ex-lover. We, too, aren't exactly sure what game Ewa is playing. She tells Janusz that her husband has gone missing and she needs help looking for him—on Christmas Eve of all days. She parks the car herself in the median but says her husband must have abandoned it. Then she calls the hospital to report her husband had been injured on the street, even though she hasn't even seen him. She does these things to string Janusz along; she's throwing a false trail of bread crumbs to keep him with her all night.

Her motives are unclear for us until the end, in part because, like Janusz, she's stringing the audience along as well. She must be lonely though, we at least know that much; her only family is a senile aunt at a retirement home. Her aunt kindly asks her about her homework and Ewa obliges—it's obvious this has become a routine by the way Ewa tries to keep a smile. This is a smile done out of courtesy, not happiness. It's a small comfort when your only family member doesn't even know your age and for Ewa, it's a slippery slope trying to keep face; her inability to maintain a smile is a dead giveaway.

Her motives are almost understandable. Her only contact with family is this rather pitiful scene with her aunt; a few minutes of humoring an old woman who doesn't even know her age. She loves her aunt—that's painstakingly clear—but it's a small consolation. Part of her is thinking: Gee, thanks [God]. I get to wake up my auntie for a few minutes on Christmas Eve only to have her fall asleep again in the middle of our "conversation." We also see Ewa stopped at a red light; she is looking at a father and son playing in the snow. Images like these are not insisted upon, but they hint at a loneliness and stasis, and make Ewa's rather bizarre, attention monger-ish behavior almost justifiable.

Janusz probably doesn't even understand Ewa's loneliness at first. Having seen Ewa eye him earlier at Mass, he knows something is up. Later, he unplugs the doorbell, hoping to avoid any surprise visits from Ewa. But she calls anyway, with Janusz apprehensive about answering the phone. He knows what awaits—or rather, he thinks he does—but goes along anyway because he wants to avoid conflict with his wife. His wife holds a similar restraint; aware that Ewa is probably calling, with the camera training on her, she stops at a distance because she isn't the contentious type.

There's a fear in her eyes; it's as if she too, knows the outcome but is incapable of stopping it. She's probably confronted Janusz before about his affair, but tonight, she can't bring herself to conflict. It could be because it's Christmas Eve and she's too surprised to act, or it might be that she's willing to let tonight's events take their course. It is the latter possibility that I find more enriching and humanist; she trusts her husband to make the right choice. As it turns out, this night will prove beneficial for everyone; providing Janusz and his wife with closure and Ewa with catharsis.

It is only when Ewa reveals her situation that her bizarre actions not only become identifiable, but more importantly, something we can empathize with. The night has been strange—almost like a mini-Eyes Wide Shut—ranging from Ewa manufacturing false clues to her husband's whereabouts, the two going to the morgue and wondering who is rejoicing the death of the man before them, Janusz fighting the sadistic guard, Ewa's suicidal attempts to drive them off the road, and the parking lot attendant skateboarding down the ramp.

It is at that parking lot that Janusz finally learns that Ewa's husband left her three years ago. For her, this has hardly been fair. They both were caught in the affair, but he gets to happily spend Christmas Eve with his wife and kids while she sits alone in her apartment. Her goal is to spend the entire night with Janusz and by the end, make him understand and empathize with her feelings. She says it's kind of like a game; she feels that if she can get through the night with Janusz, she'll be able to move on. While we may raise our eyebrows, is her superstition any stranger than our obsession with holidays or the Sabbath? If this is the way she finds closure, shouldn't we grant her that small allowance? Janusz's breaking of the 3rd Commandment effectively saves a life; Ewa drops her suicide pill, no longer needing it.

Decalogue III subverts the rigidity of the 3rd Commandment, claiming that we can't deal in absolutes. If someone needs us, then what value does the commandment have? It doesn't make sense to ignore the person standing next to you just because it's Christmas Eve. But that isn't to say the Sabbath is bad either; it, like Ewa's superstitious game, helps ground us and even proves cleansing and cathartic. In the end, Janusz and his wife achieve their closure through a simple, knowing exchange:

"Ewa?"

"Ewa."

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Decalogue II (1988)

Screenplay: Krzysztof Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz

After seeing things like Juno and 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days, it's a relief to see Decalogue II, which is so refreshingly apolitical. Juno and 4 Months bring abortion to the forefront; losing their dramatic integrity in the issue itself and in the case of Juno, the added distraction of making the characters insufferably hyper-hip. Decalogue II is such a raw, naked, and honest piece of filmmaking by comparison. It's not about the scandal of pregnancy from an affair while your husband is on his deathbed; it's about the individuals involved in this drama; their reactions and frustrations with the situation rather than the situation itself. The movie never loses sight of that.

This isn't to say Decalogue II denies of the significance of abortion as a moral issue; it's just beside the point. Sure, there's the Polish Catholic milieu to consider, but our focus in Decalogue II is on the people that populate the story. It is their fears, uncertainties, and frustrations that are so compelling because we identify with their humanity; with their moral and existential quandary. Dorota's choices carry with them such intense ramifications that to act prematurely would be devastating, should her choice be the wrong one. Abort her baby and hope her husband lives? Or keep the baby under the impression her husband will die?

Such a choice might be easier if she knew the outcome. Might be. But she doesn't, and therein lies the frustration: uncertainty. It is human to desire knowledge; to desire control; to be able to make a rational decision. It's funny how easily we can trick ourselves into thinking that everything is answerable; that somewhere out there, there is some expert or wise man who can tell us exactly what to do. For Dorota, this is the doctor. She urgently pursues him; hopeful he'll give her the answer she wants, which would be any answer other than the one he gives: he doesn't know.

Krystyna Janda is good in this role. Her face pale and gaunt, she's a woman worn down by waiting. There's an undercurrent of anger in her face, as if her own stasis has started to freeze over her ability to react. When the doctor tells her he really doesn't know what Andrzej's outcome will be, her face gives the slightest ripple of emotion. Janda's acting is the antithesis of melodrama. Like her performance in Tatarak, she is an actress of subdued expression; willing to play characters who cut close to reality and achieve a naked rawness that's genuine and beautiful.

Indeed, Janda is at once weathered and strikingly beautiful; still showing lingering vestiges of vibrance and youth in her middle-aged years. Her pregnancy is a powerful reminder of her waning years of fertility. Those years are a time bomb; counting down to Dorota's own destruction through inevitable infecundity. Things are changing around her and within her, and she yearns for control; eventually tearing the leaves off her house plant. A reminder of the relentless, plodding pace of time itself, the gesture is a helpless grasp for control; a silent outcry to stop the unstoppable. Classically Kieslowski-an, she bends the naked plant stem but it defiantly opposes her action; slowly raising itself as if to affirm the incessant beating of time.

The paradox is that as unbearable as stasis is, the alternative is a far more frightening prospect to face. Her prison becomes a refuge from the truth and reality of the situation. When she plays tapes of music, it's an attempt to escape from the burdens and consequences of action. Yet, like any escape from reality, it offers only a temporary reprieve. Decisions, death, and conclusions must be faced. Such a statement seems unbearably pessimistic and brooding, but it's not nihilism. Acknowledging chaos and uncertainty does not mean renouncing order, but rejecting an illusion.

As Myrtle Gordon from Opening Night said, what the story needs is: hope. Hope isn't wish-fulfillment. That's an important distinction to make. Wish-fulfillment tells us everything will turn out fine while making us forget harsh realities. Hope is the possibility of good outcomes in the face of trying times. Decalogue II doesn't package a cute, naive, hunky-dory conclusion because life doesn't work that way. The problem with something like Slumdog Millionaire is that it gives reality only a fleeting glance; like the person who claims they're "aware" because they've given the world news a skim. This is wish-fulfillment; a way to appease a person's guilt because they've been ignorant, but to do it in a half-assed, comforting, innocuous, politically correct way.

But at the end of the day, we needn't compare Decalogue II to inferior pictures to appreciate how beautiful a work this 50 minute movie is. Simply, to offer us hope while not diminishing reality is a rare feat. It is something to be cherished and reflected upon; a rumination on our existential woes and our inherent drive for certainty and knowledge. This frustration we have with the unknown is perpetually with us; an unrelenting reminder of our limitations as human beings. It's possible that the wonderful life we're always trying to reach---the one we keep prattling on about and filling our dreams with---will never come. We may never make it to the big time; forever working that deadend 9-5 job, but to shun reality entirely is to forgo even a chance for lasting happiness.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

Au Revoir les Enfants (1987)

The difference between narrative and plot is such an important one that it's frustrating to see movies stress the latter at the expense of the former. Plot hardly guarantees a compelling narrative, and too often, the feel of the story is lost in the mechanics. How refreshing then, to see Au Revoir les Enfants again; a movie that tells its story through character and atmosphere, not plot. Rather than create melodrama, Au Revoir builds understanding through loosely connected vignettes shot from the wide-eyed innocence of a schoolboy. A very naturalistic way of storytelling, this method develops characters as we would actually get to know them. Movies too often give us shallow fantasies with simplified, yet attractive caricatures; slices of wish-fulfillment that have little bearing to reality. In truth, we rarely get acquainted with people through a singular plot of connected events, but through random, loosely connected encounters. Thus, it makes sense that Au Revoir gives us such a strong understanding and feel for its characters. This is a movie that makes the apparatus of movies disappear; pulling us into a specific time and place and a hardened reality.

It is the characterization that makes Au Revoir so compelling. The schoolboys are self-absorbed; not yet capable of comprehending the bigotry and violence of the period (and to an extent, can we?). To them, an air raid doesn't inspire fear, but is rather a welcome reprieve from the stuffiness of the classroom. When they shelter themselves in the cellar, Jean Bonnet asks Julien for some light, but Julien refuses, burying himself still further in his book. There is little self-sacrifice or altruism to be had, and among the children, there is none. This isn't in itself blameworthy, but a natural tendency in our adolescent years. It is but one facet of the human condition. Even Jean, who is more awake to the dangers Jews must face, doesn't act with the responsibility of an adult. To imbue him completely with solemn-faced maturity would be to deny him any semblance of humanity. This humanity rings true when, during an air raid, Jean and Julien ditch the safety of the cellar to play jazz duets on the piano.

Such a moment is so easily exploited for melodrama that it is a relief when it passes inconsequentially. Instead of having the priests reprimand Jean and Julien, the film quietly cuts to the next scene. There are many moments like this in Au Revoir; where the action can be pushed into melodramatic confrontation. Such handling of these situations would destroy the evocative sense the movie brings. This is a picture set in the past, and is more of a recalling of events long gone than an immediate, cohesive, in-your-face plot progression. Which isn't to say that plot is irrelevant; just that it's not insisted upon.

There are great movies that make the camera come alive and great movies that make it disappear. Au Revoir is the latter; making the screen disappear entirely and fully integrating the viewer into the movie's world. Too often, emphasis on mise en scene and "cinematic language" dominate the evaluation of a movie. Yet analyses dependent on these devices alone, while fascinating, rarely point out what really affects us about these pictures. While the value of such observations shouldn't be ignored, they can't be the sole source of meaning. Roger Ebert is proud of his "cinema interruptus," but shot-by-shot analysis is a coldly intellectual process that distances the viewer from the material. It becomes too much of a game; trying to decided what the director's "intentions" were and the feel of the story gets lost, not in the mechanics of plot this time but the mechanics of moviemaking itself.

Friday, March 12, 2010

...Around (2008)

The movie about a filmmaker struggling to make a picture but suffering some sort of creative block (i.e., a movie about itself) can be tiresome. Often, self-reflexive cinema is a chance to make something seem more insightful than it actually is. It’s as if the film’s awareness of itself is all that's needed to validate its artistic integrity. Yet what are the filmmakers actually saying? There are plenty of amazing and insightful movie-movies that use the subject of film as a springboard into more complex discussions. But it is so easy to get so caught up in cute little self-reflexive moments and lose sight of the larger, more meaningful implications. As Kael points out in her review of Fellini’s 8 1/2, the filmmaker is searching for some vague “idea.” What makes him a genius if he is so dependent on the epiphany of this one idea? I’m not quite as harsh as Kael is towards 8 1/2 and various other “party” movies she despises so much. But I’ve never embraced Fellini’s film like so many others because the focus is on the search for this one vague, self-centered, silly idea, and a lot of the meaning and feeling of the picture gets lost in the clever-looking shuffle.

So it was with a little apprehension that I approached David Spaltro’s directorial debut: …Around. It’s about a young man going to film school and forced to live on the streets since all his money is for tuition. Throughout this experience, he picks up friends, mentors, and love interests along the way.

The first 10 minutes or so don’t work. We see his parents explaining to him and his sister why they’re separating, his father choking up in the car, him getting in trouble at school, etc.. The point is, we see these scenes and recognize their significance but we aren’t allowed to really feel and inhabit them. Part of the problem, I think, is in the acting. Young Doyle’s lines aren’t delivered naturally, but with an awareness and bashfulness in front of the camera. Yet the big problem may be Doyle’s father. Too often I sensed the actor forcing, rather than becoming, the role. His facial expression showed “sadness” in the car scene, but it felt like a parody of emotion rather than a genuine expression of feeling. But that isn’t to say these first few minutes are without value. The scene with Doyle in his room, listening to his parents, is handled with the same poignancy as The 400 Blows.

Yet it is when Doyle emerges from the New York subway that the movie finally breathes and shakes off its awkwardness. The humor no longer feels so contrived, and you get the sense Spaltro is in his element. This is a picture that breathes of New York, and the pillow shots add to its authenticity and flavor. That atmosphere is focused around film school for the first year, and it’s refreshing to see something that’s willing to make fun of its own milieu. The movie giddily pokes fun at up-and-coming, buzzword-dropping young art students. The best kind of art, as Kael said, is playful.

Yet the movie’s strength lies in providing a formative, tragicomic human experience in lieu of exploring the director’s disembodied genius. That is, the movie becomes emotionally and socially relevant; not merely intellectual, but providing us with insight into how we live and interact with others. Doyle is intensely romantic; wanting to rescue Allyson from her possessive, overbearing boyfriend but not to commit to a serious relationship. Like Clark Gable in Gone with the Wind, he loves being the guy to kiss the girl, then leave in some noble pursuit. Only his civil war is an internal one; stemming from a need to understand himself before he commits to others. As he says to the mirror: “What’re you gonna do?” and “Hello stranger.” Part of that self-discovery comes when he confronts his mother on her deathbed. It doesn't quite offer the satisfaction we would like and the awkwardness with which Doyle tries to say "mom" is genuinely uncomfortable. That is, of course, its strength; satisfying moments in Hollywood movies, on the other hand, grant us the wish fulfillment we crave but not necessarily the one we actually get or deserve.

Spaltro has assembled a good cast that, for the most part, delivers their lines fluidly and naturally. Rob Evans has a passivity à la Edward Norton in The 25th Hour, where he’s taking a step back from the world and watching it go by. Doyle’s life, like Monty Brogan’s, is on hold. Molly Ryman shows promise, too. Her performance, however, is more hit-or-miss, and there are moments where she seems to come out of character and become aware of the camera. Yet when she hits the mark, it's a bull's-eye. She looks off-screen in the pensive, vulnerable sort of way Ingrid Bergman would.

David Spaltro shows promise. …Around is a vibrant, playful movie that brings some integrity to the Indie picture’s visual reputation. Lately, indiscriminate handheld work has passed for a “documentary” or “Indie” feel even when the dramatic or thematic elements of the picture don’t really call for it. Spaltro does not kill the picture with technique. For the most part, he uses it to underline the dramatic action of the story. …Around is a good start, and I hope David Spaltro only improves from here.

Saturday, March 6, 2010

War of the Worlds (2005)

Screenplay: Josh Friedman and David Koepp (based on the novel by H.G. Wells)

Starring: Tom Cruise, Dakota Fanning, Justin Chatwin and Miranda Otto

Steven Spielberg's War of the Worlds is a severely misunderstood work. Praised or dismissed as a summer blockbuster, the movie deserves reconsideration as a timely work of art; a post-9/11 allegory reflecting a climate of shock, confusion, and fear. Cahiers' placement of War of the Worlds as the 8th best picture of the decade is a step in the right direction. Hopefully, this choice will not be met with kneejerk skepticism, but with thoughtful revision. War of the Worlds is a movie that can't be analyzed so much as felt, and it holds special resonance with our post-9/11 generation. If ever there is a work capable of invoking our nationalistic sentiments in a non-exploitative manner, then War of the Worlds may be it. That it achieves this as a blockbuster is amazing; balancing simultaneously as entertainment and as an expression of contemporary sentiments.

Roger Ebert makes some astute observations in his review of the movie, but fails to understand their implications. He complains the aliens aren't believable or interesting, describing their invasion as "pointless" and concluding:

"The thing is, we never believe the tripods and their invasion are practical... It's a war of the worlds, all right -- but at a molecular, not a planetary level... A planet that harbors intelligent and subtle ideas for science fiction movies is invaded in this film by an ungainly Erector set."

Criticizing the aliens for purposelessness and adhering to a monomaniacal rule that the aliens need recognizable motives misses the point. The aliens and their tripods are not an extraterrestrial threat so much as a metaphor of man's capacity for war; pure violence incarnate. Note that the alien tripods do not "land" from outer space but come up from beneath our cities and our homes, suggesting they have been with us all this time. Symbolically, they are not an external threat but represent the inner chaos and capacity for destruction that lies beneath a seemingly benign and civil facade. The "war" the title suggests is not a macroscopic fight between man and alien. Rather, it takes place, as Ebert said, on the molecular level; an internal "fight" between man's polarizing tendencies towards violence and nonviolence. The picture becomes a roadsign; cautioning us against reactionary violence and eye-for-an-eye. It’s not simply preaching anti-violence, but rather asking us to proceed with caution and ask ourselves where our responsibilities lay.

The pointlessness of the alien attacks is necessary for meaning and emphasizes the nonsensical, inexplicable consequences of violence. Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise) finds himself at a loss for words. How does he explain to his children the horrors he's witnessed? How do you explain people not just being killed, but vaporized into ash all around you? To insist that such violence needs "purpose" borders reprehensibility. While I understand Ebert's complaint with respect to narrative, he inadvertently advocates violence in the process by trying to rationalize it. War is rarely so clear-cut. You often hear of veterans after the war, saying how nobody even remembers why it started. The same applies here. It becomes very easy to stray from the path we set out upon; to lose our sense of purpose and wander aimlessly into battle.

Spielberg is not making another Close Encounters of the Third Kind or E.T.: The Extraterrestrial, where aliens invoked genuine beauty and wonderment. In War of the Worlds, the aliens and their tripods are supposed to be ungainly. As avatars of violence, their grotesquery and instability make sense. War of the Worlds proposes the apocalypse, but its strength lies in balancing on the precipice between a life-affirming, yet cautious optimism, and a meaningless, nihilistic void. Violence can be overcome and it does have weaknesses. The movie offers us hope that chaos is not invincible and affirms the existence of harmony and humanism in the universe.

Somehow, War of the Worlds is criticized for a lack of emotion. This becomes difficult for me to understand because when I recently watched the movie again, I was struck by how poignant these images were, in part because they are tied to my own sense of nationalism. When Ray takes his kids to his ex-wife’s house and the plane hits, Spielberg is reenacting 9/11 on an expressionistic microcosm. Tragic events like these bring the child to the forefront. On one level, the urge to shield our children from the horrors of violence becomes an anchor; grounding us from the ensuing chaos. On another level, these events make us all like children; regarding violence with wide-eyed shock. Such concepts are hardly shallow, and how critics can ignore or belittle them is beyond me. These same critics go on to criticize the 9/11 allusions as exploitation. So contemporary issues are taboo for blockbusters? The mainstream picture can't be art? You can only deal with these issues in a literal sense? Preferably via "independent" filmmakers with shaky camera work? Is the allegory dying, or is it already dead?

Critics who say the movie lacks emotion must have ice water in their veins. Not that they don't feel anything, but they resist and reject that emotional pull. 9/11 is unacceptable subject matter, not because of how it's handled, but because it makes us uncomfortable and blockbusters can't be serious. Yet War of the Worlds is not using 9/11 for cheap thrills, but as a springboard into discussing violence and our national atmosphere. It, along with Minority Report and Eastern Promises, present unique and sound approaches to violence in an age where death (and rape) become ever more casual in the movies and on TV. If it makes violence uncomfortable, it's doing its job. Those three movies handle violence effectively because they do not rely on increasing detail or raising body count. Minority Report is essentially a thesis on violence, setting up a hypothetical world where murder is virtually nonexistent. A death in Minority Report shocks us and resonates deeply, because the world of the movie has convinced us murder doesn't exist; lulling us into a sense of security. Eastern Promises, as I've written before, doesn't pile up a faceless body count. Each act of violence is tied to the dramatic and emotional arc of the picture. And War of the Worlds. The overwhelming loss of innocent human life is intensified by those 9/11 allusions. What would you rather have: a blockbuster that belittles human life for entertainment (Lord of the Rings), or one that presents violence that does disturb us?

War of the Worlds is not a picture that relies on its narrative so much as the images it presents. Ray with his daughter, watching the storm brewing in the distance evokes our false sense of impunity before 9/11; the illusion that the US was invulnerable to attack. It’s not simply the attacks of 9/11, but the falling popularity of our subsequent actions. 9/11 was a slap in the face; a wakeup call that War of the Worlds captures magnificently. Other images, like Ray seeing people turn to ash all around him, his speechlessness afterwords, or his frustrations as he tries to fulfill his role as a parent are humanist at their heart. Ray is not looking for vengeance but to protect basic human values. These values are tested and their complexity is enriched when he needs to kill Harlan Ogilvy (Tim Robbins) in order to protect his daughter. War of the Worlds is not a black and white message movie offering simplistic morals to complex situations. If the movie has plausibility, it lies in its characters’ actions. These are believable reactions to a state of chaos and cover a vivified spectrum of human nature. There is a desire to seek vengeance, protect our children, stare in wide-eyed wonderment, clamor for our own safety, act with benevolence, or go mad.

The mainstream picture is denied contemporary allusion whenever the critics feel like it. Not because of how it handles the material, but because of what it inherently is. It depends on who's in the movie and who directed or funded it. War of the Worlds is socially conscious and moralistically sound; its metaphor of violence is hardly outrageous or blameworthy. I don't even think it's a partisan picture. And somehow it receives more flak than subversive, politically biased, poorly constructed messes like Slumdog Millionaire or Avatar.

War of the Worlds is a movie that must be felt. Analyzing it shot-by-shot can be done, but such a method is reductive and runs the risk of losing the feel of the work. Rejecting a movie simply because it invokes our nationalist sentiments reeks of elitism; arbitrary rules are put in place dictating what gets put on the pedestal of Art and what's throwaway entertainment.

"Are we still alive?"

-Rachel